POC and OTC Devices: Rapid Microfluidic Technology on Drugstore Shelves

On the shelves of virtually every drugstore in the world are small products that have a big impact. What are they? There are home-use diagnostic tests for drugs, ovulation and—perhaps the most familiar—tests for pregnancy. What do these tests have in common? Simple, inexpensive, easy-to-use, these tests all use of lateral flow assay (LFA) technology, often “over-the-counter” (OTC) or as “point-of-care” (POC) diagnostic tests.

Traditionally, diagnostic testing is done in distant, sophisticated laboratories using expensive equipment, performed by trained personnel and ordered by licensed physicians. Contrast that with how a home-use OTC diagnostic test, such as a pregnancy test is used: the equipment required is the test itself. The only training the user needs is a small piece of paper with instructions. An unmeasured sample of urine is applied to the device, followed by a brief incubation period. Then the test is read with the naked human eye.

How Do Lateral Flow Assays Work in POC and OTC Devices?

This test may seem simple, but the science behind these LFAs is impressive. The molecule that is being tested in the home pregnancy test is human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). It is produced by the fertilized egg and helps prepare the mother’s body for the pregnancy. It is either absent or present in extremely low concentrations in women who are not pregnant. A level of 20 milli-International Units per milliliter (mIU/mL) of urine is indicative of an active pregnancy. This is equivalent to a concentration of about 5×10-10 moles per liter (M).

Here’s a thought experiment to show just how sensitive this test is: a single sugar cube weighs about 2.8 grams, and the sucrose in it has a molecular weight of 340 grams per mole. That means that a sugar cube has about 5×10^21 molecules, or 0.0082 moles of sucrose. How many liters of water would it take to dissolve that amount of sucrose to a concentration equivalent to the sensitivity of the OTC pregnancy test? A quick calculation indicates it would take about 16 million liters (roughly six Olympic-size swimming pools) to dissolve a single sugar cube to the equivalent concentration of hCG detected in a pregnancy test.

A positive home pregnancy test will show two colored lines: a test line and a control line. The control line indicates that enough sample was added and that the test ran as designed. A negative test shows only one line at the control line. If no colored lines are visible, it means that an insufficient amount of sample was most likely applied to the device and the test is invalid.

OTC and POC Lateral Flow Technologies

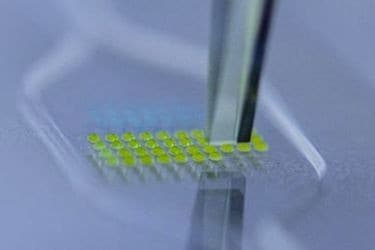

Though these tests seem simple, they make use of plastics, dye technology, animal proteins, and chemistry: a combination of ingredients that rivals many inventions from MacGyver of television fame. Experimental animals such as mice or rabbits are injected with hCG, much like when humans get a flu shot. The animal’s immune system recognizes the human hCG as foreign and mounts a defense against the invader including the production of antibodies which are blood proteins that bind very specifically to the foreign molecule. These antibodies are harvested from the animal and used as reagents or chemicals to recognize and bind to the foreign molecule. They can be extremely specific and will not bind to closely related molecules. In manufacturing, some of these antibodies are chemically bound to a long, thin strip of porous material called nitrocellulose. The antibodies are immobilized in a line perpendicular to the long axis of the strip. This constitutes the test line.

Other antibodies are chemically derivatized with very bright dye molecules or nanobeads with many dye molecules, and then applied loosely to the strip. Another line of antibodies raised in another animal like a goat that recognize the mouse or rabbit antibodies are applied in another line perpendicular to the long axis of the strip further down the strip of nitrocellulose. This is the control line. These reagents are applied to the strip in manufacturing, stabilized for long shelf life and enclosed in a plastic cassette. To use the device, a urine sample is applied to one end of the porous strip and begins to wick along the strip by capillary action. The urine sample first encounters the loosely-bound labeled antibodies and dissolves them in the sample. If hCG is present, the labeled antibodies bind to the hCG to form an immune complex. Capillary flow continues and carries these immune complexes to the line of immobilized antibodies which recognize the hCG and react with the complexes and keep them from moving further. This constitutes the test line. Labeled antibodies that do not have any hCG bound to them continue to move with the flow until they encounter the goat anti-mouse line and are stopped. This constitutes the control line. At that point:

• If there is not enough fluid sample added, none of the lines will show color.

• If there is insufficient hCG in the sample, only the control line will show color.

• If there is sufficient hCG in the sample, then both the test line and the control line will be colored.

Many other LFAs are used in human clinical diagnostics, including infectious disease detection and monitoring in a doctor’s office. This application is different from the pregnancy test example in that several tests are done per week. That means that it makes economic sense to invest in a reader device. Using instrumentation other than the human eye to read the test increases the assay sensitivity because other detection technologies such as fluorescence can be employed. Assay precision also increases with the use of instrumentation.

COVID-19 Pandemic: The Need for POC and OTC Testing

With the COVID-19 pandemic, the world has become much more familiar with LFAs. The press often refers to them as “point-of-care” or “finger stick” tests. A new flood of LFAs for the detection of the virus or antibodies to COVID-19 has hit the market. Given the pressing need to get validated tests into the hands of medical professionals and others to aid in diagnosis and case tracking, the FDA, which regulates all medical diagnostics in the U.S., has issued Emergency Use Authorizations (EUA) to a number of manufacturers. These EUAs have allowed companies to commercialize and sell these tests on accelerated timelines, albeit including some products of questionable accuracy.

The take-home lesson from this is that not all LFAs are created equal and that crafting a quality LFA takes time and expertise in different disciplines. It demands a detailed understanding of the disease conditions or organisms that the test is intended to detect and the characteristics of the population to be tested. For example, if a test has a false positive rate of 1%, it may be useful if 30% of the population has the condition, but it would not if only 2% of the population had the disease. It takes a deep understanding of all the materials that go into an LFA, including the antibodies, the labels, the nitrocellulose solid support and even the plastic parts that make up the cassette. A few LFAs can be assembled manually, but making commercially significant quantities of tests requires intelligent automation that must be acquired, calibrated and maintained to ensure product quality. Products should be developed with manufacturing in mind from the beginning as it (manufacturability) is difficult and costly to incorporate after development. Finally, the usability of the product is of utmost importance. These devices must be designed with the end-user in mind.

If an organization lacks the necessary expertise to design a quality LFA-based product, it makes sense to partner with someone who can help manage that process—including engineering, usability testing, and well-executed organization of clinical studies that are especially critical when preparing for regulatory approvals. We have helped companies succeed in developing LFA-based diagnostics for years. A conversation with our team of engineers, clinical researchers and regulatory experts could help you enhance your chances of launching a successful diagnostic product.